|

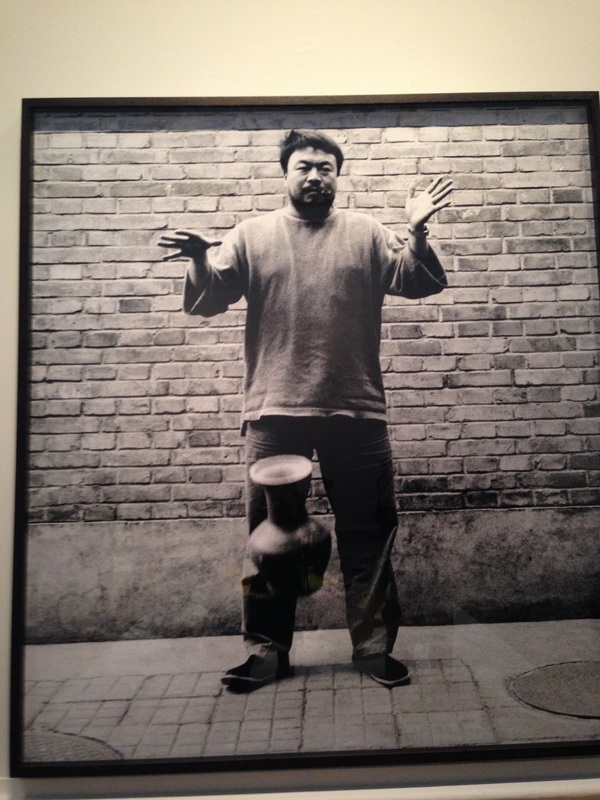

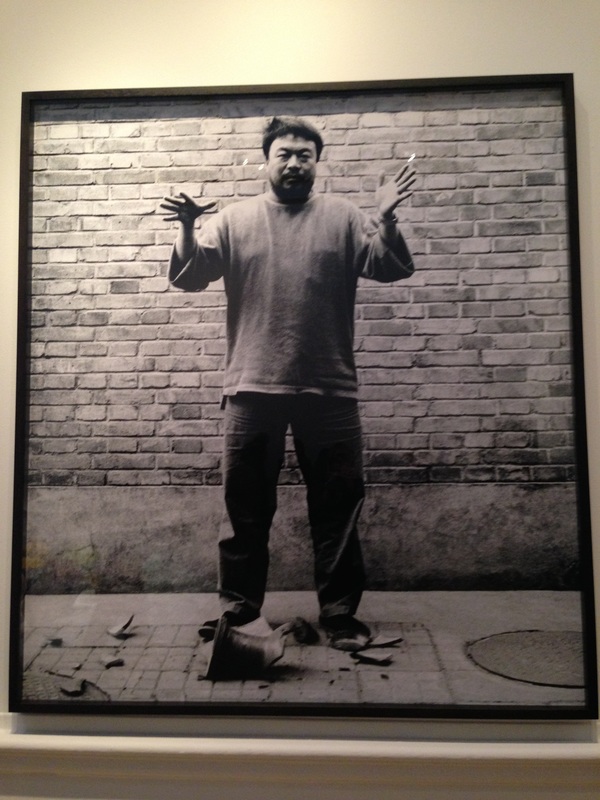

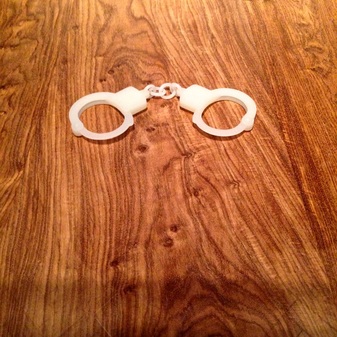

Prior to my year abroad in Wuhan, an industrialized city of 9 million in the center of the country, “China” was more or less an abstract concept to me. I had read about the censorship, environmental and human rights concerns; I had watched the bombastic spectacle of the 2008 Beijing Olympics; I had spoken with friends from Hong Kong or Singapore who visited the mainland frequently; I had studied pieces of its tumultuous history. It was all much too big, too far and too foreign for it to resonate on an emotional level though. How can one connect with more than 1.3 billion strangers? It wasn’t until I touched down in Shanghai and later in my far less westernized adopted hometown that certain things started to sink in. The sheer scale of the cities is daunting—buildings in Beijing appear closer than they are due to their impossible, improbable size. The crush of a seemingly infinite number of bodies at every train station, on every public holiday, at every monument, makes the mind reel. “China has too many people,” I was often told, and there is a constant sense that there might not be enough resources for everyone. As a teacher at a large university, my actions were monitored at all times. There were cameras in my classroom, cameras in the halls, cameras throughout the campus and cameras near my apartment. On each floor of each school building, a man or woman sat blankly staring at a moving black-and-white wall of security footage. And while the concept that all digital communications are subject to government scrutiny now, sadly, is no longer shocking, in 2010 it was unsettling to filter all email and Skype messages, even when using a VPN. During this time, Ai Weiwei was very much a name on everyone’s lips. He had become increasingly vocal in the wake of the 2008 Sichuan earthquake and, though his international prominence protected him, many whispered that his actions would not be tolerated for long. Liu Xiaobo had already been imprisoned and the government was cracking down on human rights activists previously thought to be immune. I make no pretense of being an expert on this vast and vastly complex nation, but I have a deep respect for the courage it takes to speak out there. Even then in Wuhan, there were small signs of subversion—“1989” scrawled on walls, hushed political discussions, covert reading of uncensored foreign publications, students throwing their Communist party pins to the ground. Even the smallest actions were done carefully, with the knowledge that there might be consequences. And though ordinary citizens could never dare to do what famous artists did, Ai Weiwei's public provocations had a powerful impact. All of this is my rather long-winded way of saying that I admire what the artist was willing to risk and what he has been able to accomplish. Purely by coincidence, I bumped into the man himself towards the tail end of summer in Berlin. He had recently arrived in the city and had stopped for a drink at Café am Neuen See. He’s a bear of a man and a number of other guests had taken note of his presence and already stopped by to say hello. Patiently, politely, he took the time to greet them as they came. I didn’t want to bother him for long and I certainly didn’t want to inflict my bastardized Mandarin on him, but it was an honor to shake his hand and listen to him, however briefly. As much as I admire him on a personal level though, I had less of a fully developed opinion on his actual art. I had read about the concepts behind his major works, but seeing a little clipping in a newspaper is a poor substitute and I was eager to get a look at the real thing. So on a recent visit to London, I made sure to stop by the Royal Academy of Arts for his current exhibition (through December 13). Thoughtfull, ambitious and, for me at least, moving, it’s worth seeking out (be sure to book ahead) if you have the opportunity to see it. I won’t bother with a full blow-by-blow, as more knowledgeable individuals have already done that, but here were a few of the highlights. StraightInterestingly, many of the workers who were hammering away at these for years had no idea what the idea behind the project was or the significance/origin of the materials. By far the most powerful piece for me, even if it’s not as aesthetically appealing as some of the others. The 90 metric tonnes of rusted rebar here were collected from the fallen schools in the 2008 Sichuan earthquake, hammered over 200 times each until almost returned to their original state, then laid out in a kind of eerie landscape juxtaposed with the names of the dead children. There’s a palpable feeling of grief and rage upon entering the room, even before delving into the commentary. He XieThis one was one of my favorites, primarily because at first glance it appears to be something else. The pile of thousands of brightly colored river crabs initially looks like a heap of cheap, mass-produced toys. In reality, each of these individually crafted porcelain crustaceans took a great deal of labor to produce. He xie, the word for river crabs, sounds like the Mandarin word for “harmony,” which is often used as slang for government propaganda. On the night before the demolition of his Shanghai studio, Ai Weiwei invited everyone to a studio party to feast on he xie. A good 800 turned up in support, even though the artist himself could not be present. TreeImmense and immersive. More "trees" can be found outside the museum. A huge installation of twisting branches and trunks formed from old temple pillars. From above, it resembles a map of China (a recurring theme in other works such as Bed), with two conjoined stools standing in for Taiwan. Marble StrollerFor me, his works in jade and marble, which include sex toys, handcuffs and this intricate stroller on a field of thousands of unique blades of grass, call into question the idea of an artist versus an artisan. One of the things I find most interesting about classical painting or sculpture is the actual technique that went into it. I like examining the brushstrokes on a Velasquez or the chisel marks on an unfinished Michelangelo. Most of the manual labor in Ai Weiwei’s work, however, is done by other highly skilled craftsmen. Outsourcing some of the more repetitive tasks isn’t that new though—the grunt work of painting backgrounds and details in works by Rubens and other old masters was often done by apprentices or lesser-known artists from their studios—and the technical skill of others here allows the artist to realize a more ambitious vision than he could produce alone. This particular item was inspired by the government's surveillance of his son. S.A.C.R.E.D.One of the most literal of the collection, this series of six dioramas, each one half the size of the actual cell where the artist spent 81 harrowing days, S.A.C.R.E.D. is easily one of the most uncomfortable. Visitors peer through peepholes into scenes from his personal hell, including eating, sleeping, showering and interrogation, all while accompanied by two guards. There’s a voyeuristic feeling to it all and the meticulous attention to detail makes it all too real. I found the custom-made wallpaper work Golden Age, with the Twitter symbol and security cameras, to be a bit heavy-handed when paired with this particular piece, although it’s an interesting work in its own right. Bicycle Chandelier Visually speaking, this one is a stunner and there’s a reason the curators saved it for last. The classic Chinese bicycle frames that make up the crystal chandelier nicely tie in thematically with his other repurposed works.

1 Comment

7/29/2023 06:59:26 am

I wanted to express my gratitude for your insightful and engaging article. Your writing is clear and easy to follow, and I appreciated the way you presented your ideas in a thoughtful and organized manner. Your analysis was both thought-provoking and well-researched, and I enjoyed the real-life examples you used to illustrate your points. Your article has provided me with a fresh perspective on the subject matter and has inspired me to think more deeply about this topic.

Reply

Leave a Reply. |

RSS Feed

RSS Feed